Sir Review

Suggestions

Can watch again

No

Good for kids

No

Good for dates

No

Wait for OTT

Yes

I don't remember the last time I saw a movie where the hero gets exiled from his town in a dramatic manner. (I'm discounting the last scene of Prince, because it was a travesty.) I'm talking about a proper old-fashioned banishment, like in Chiranjeevi's Indra and Rajnikanth's Narasimha, where the shamed protagonist slow-walks, barefoot in the hot sun, to the nearest bus stop, while the townspeople stare at him mutely. Maybe it is overwrought scenes like this or because the movie is set in the '90s, but watching Sir felt like riding a time machine two decades into the past. Back to the days when cinema stories were built on idealism, black-and-white morals and God-like heroes.

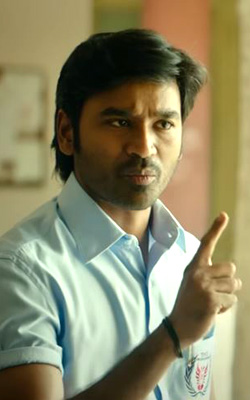

I know you are thinking, "Wait, don't our stars still possess otherwordly traits?" They do - when it comes to the physical stuff. But on morality, they've degraded somewhat, haven't they? Today's heroes won't stand and orate as much as they fight and eviscerate. They won't be sacrificial lambs - they lead revolutions. They certainly aren't like Balu, the protagonist of Sir (Dhanush) - eager, humble, and relentlessly optimistic.

Venky Atluri's Sir is the story of a lone teacher's fight to provide a decent education to government school students. Like John Keating from Dead Poet's Society, or Katherine Watson from Monalisa Smile, Balu Sir is a maverick stuck inside a rigged institution. On Day One of his job as a junior lecturer, he wins over the town's small-minded parents with a snappy speech on the life-changing magic of education in which he recalls the origin story of - you guessed it - Dr Abdul Kalaam. Day Two: he wins over his students with a clever demonstration of the ineffectiveness of the caste system. By the end of the semester, he is a much-beloved figure. And this makes one Mr Tripathi (Samuthirakani), the greedy ringleader of the state's largest chain of private colleges, very nervous.

Tripathi has built his empire convincing parents that more money equals better education. Now Balu threatens to publicly prove him wrong by teaching for a pittance and refusing to sell his soul. Tripathi launches a quiet campaign to break Balu's spirit and scare him out of his job.

Atluri's script is contrived to be a tear-jerker at every turn of the page, but personally, I found it impossible to squeeze out even a drop. For one thing, the writing feels agenda-driven, with any character or trait that doesn't serve this higher purpose unceremoniously discarded. Balu's lecturer friends, who act as the comic relief for the first half of the movie, literally pack up and leave when the story takes on a more serious tone.

Atluri sees no need to create fully realized, complex characters - like those in a fable, they embody certain ideas or virtues. Tripathi is incorrigibly evil. Balu is a Gandhian idealist. Balu has a love interest, a homely biology teacher named Kavitha or Kalpana or Kavya (Samyuktha Menon) - her name doesn't really matter because his one true love are his students for whom he is willing to risk his life.

These students return the favour by being even more caricaturish in their adoration of him. Unlike any teenagers in human history, they are remarkably obedient and easily influenced. They admire Sir and weep for him when he gets sent away. And every last one of them becomes a grade-A student under his tutelage.

So what high-and-mighty agenda justifies such distortions of reality? Atluri takes aim at India's often-corrupt and predatory education system. But he is smart enough to know that revolutions don't happen overnight. As shown repeatedly in the story, they require a smart strategy (don't fight the system, exploit it right back) executed by a capable leader (Balu Sir) willing to go down with the ship.

Too bad, though, that while this strategy feels fresh, boosted by some very well-written lines, it is overreliant on melodrama. Every few scenes someone is crying or having a change of heart. To rephrase a line one repentant character says mid-transformation, "Dhurmarganiki kuda oka haddhu undali" (even corruption must have its limits) - well, dear Atluri, overaction ki kuda oka haddhu undali, sir.

If hamminess is an inherent trait in Sir's characters, then they might as well cast the best men to play them. Dhanush and Samuthikiran, along with Sai Kiran who plays the burly village President, put on remarkable performances. Samyuktha Menon however feels like an overhang, and her acting is unrefined.

Sir is a soppy tale of epic emotionality of the kind that feels archaic in today's cinematic landscape. It could surely have made a greater impact with less theatrics and more levity.

I know you are thinking, "Wait, don't our stars still possess otherwordly traits?" They do - when it comes to the physical stuff. But on morality, they've degraded somewhat, haven't they? Today's heroes won't stand and orate as much as they fight and eviscerate. They won't be sacrificial lambs - they lead revolutions. They certainly aren't like Balu, the protagonist of Sir (Dhanush) - eager, humble, and relentlessly optimistic.

Venky Atluri's Sir is the story of a lone teacher's fight to provide a decent education to government school students. Like John Keating from Dead Poet's Society, or Katherine Watson from Monalisa Smile, Balu Sir is a maverick stuck inside a rigged institution. On Day One of his job as a junior lecturer, he wins over the town's small-minded parents with a snappy speech on the life-changing magic of education in which he recalls the origin story of - you guessed it - Dr Abdul Kalaam. Day Two: he wins over his students with a clever demonstration of the ineffectiveness of the caste system. By the end of the semester, he is a much-beloved figure. And this makes one Mr Tripathi (Samuthirakani), the greedy ringleader of the state's largest chain of private colleges, very nervous.

Tripathi has built his empire convincing parents that more money equals better education. Now Balu threatens to publicly prove him wrong by teaching for a pittance and refusing to sell his soul. Tripathi launches a quiet campaign to break Balu's spirit and scare him out of his job.

Atluri's script is contrived to be a tear-jerker at every turn of the page, but personally, I found it impossible to squeeze out even a drop. For one thing, the writing feels agenda-driven, with any character or trait that doesn't serve this higher purpose unceremoniously discarded. Balu's lecturer friends, who act as the comic relief for the first half of the movie, literally pack up and leave when the story takes on a more serious tone.

Atluri sees no need to create fully realized, complex characters - like those in a fable, they embody certain ideas or virtues. Tripathi is incorrigibly evil. Balu is a Gandhian idealist. Balu has a love interest, a homely biology teacher named Kavitha or Kalpana or Kavya (Samyuktha Menon) - her name doesn't really matter because his one true love are his students for whom he is willing to risk his life.

These students return the favour by being even more caricaturish in their adoration of him. Unlike any teenagers in human history, they are remarkably obedient and easily influenced. They admire Sir and weep for him when he gets sent away. And every last one of them becomes a grade-A student under his tutelage.

So what high-and-mighty agenda justifies such distortions of reality? Atluri takes aim at India's often-corrupt and predatory education system. But he is smart enough to know that revolutions don't happen overnight. As shown repeatedly in the story, they require a smart strategy (don't fight the system, exploit it right back) executed by a capable leader (Balu Sir) willing to go down with the ship.

Too bad, though, that while this strategy feels fresh, boosted by some very well-written lines, it is overreliant on melodrama. Every few scenes someone is crying or having a change of heart. To rephrase a line one repentant character says mid-transformation, "Dhurmarganiki kuda oka haddhu undali" (even corruption must have its limits) - well, dear Atluri, overaction ki kuda oka haddhu undali, sir.

If hamminess is an inherent trait in Sir's characters, then they might as well cast the best men to play them. Dhanush and Samuthikiran, along with Sai Kiran who plays the burly village President, put on remarkable performances. Samyuktha Menon however feels like an overhang, and her acting is unrefined.

Sir is a soppy tale of epic emotionality of the kind that feels archaic in today's cinematic landscape. It could surely have made a greater impact with less theatrics and more levity.

SIR USER REVIEWS

Be the first to comment on Sir! Just use the simple form below.

LEAVE A COMMENT

fullhyd.com has 700,000+ monthly visits. Tell Hyderabad what you feel about Sir!

MORE MOVIES

SEARCH MOVIES

Dissatisfied with the results? Report a problem or error, or add a listing.

ADVERTISEMENT

SHOUTBOX!

{{ todo.summary }}... expand »

{{ todo.text }}

« collapse

First | Prev |

1 2 3

{{current_page-1}} {{current_page}} {{current_page+1}}

{{last_page-2}} {{last_page-1}} {{last_page}}

| Next | Last

{{todos[0].name}}

{{todos[0].text}}

ADVERTISEMENT

This page was tagged for

Sir telugu movie

Sir reviews

release date

Dhanush, Samyuktha Menon

theatres list