Article 15 Review

Suggestions

Can watch again

No

Good for kids

No

Good for dates

Yes

Wait for OTT

No

Before we discuss the highs and lows of Anubhav Sinha's newest film, I would like to share a couple of personal anecdotes. Nearly 15 years ago, my family and I were returning home after a week-long stay at our native village. As we began our journey, the village's local Brahmin crossed our way. My uncle made it a point to halt all further proceeding for 15 minutes as it was a bad omen to have a lone Brahmin cross one's path when one was embarking upon a journey. A man who routinely questioned the existence of the big man in the sky was the one harbouring this superstition.

Nearly a year ago, my girlfriend and I spoke to both sets of parents about our relationship. For all the support they showed my cousins when they came clean about their relationships, one of the first concerns raised by my parents was, "We hope her family isn't too far down the caste ladder because it'll be a hard thing to justify to our relatives." Need I remind you, this happened in 2018.

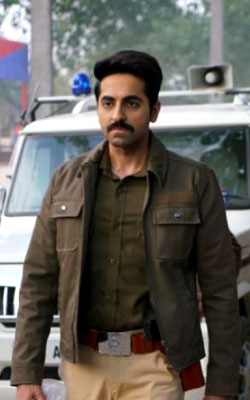

As much as we city slickers try to turn the blind eye to it, prejudice does exist all around us. Your experience with it might be wholly different when compared to mine but denial is not an option. Ayushmann Khurrana's Ayan Ranjan, too, is one of us. A Delhi-bred, foreign-educated, millennial, woke, IPS officer that does not see caste. His first posting is to the sleepy, mist-filled, fictional town of Laalgaon in rural Uttar Pradesh. Akin to you and me, the townsfolk make the fictional Ayan aware of their locality's stringently upheld caste system with the use of both actions and words.

A day later, three teen girls, from one of the lower castes, are reported missing. A day after that, two of the three girls are found hung by the neck on a lonely tree. Armed with a police force that seems hellbent upon closing the case without a shred of investigation, Ayan takes it upon himself to deliver justice to the marginalised section of Laalgaon's population.

Both Ayan and the film he is in have universally beloved ideals. But simply having high ideals doesn't give a film a perfect score. High ideals need to be bolstered by high-level filmmaking and storytelling. Article 15 does the first part well right off the bat. The film's exquisite cinematography and sense of mood, tone and space set you up for the noir-inspired cinematic experience. The score is ominous, the shot division is pitch perfect, the set design and costumes are on point, and the social message being espoused is relevant to the present day.

In the vein of Sanjana's mom in Main Prem Ki Deewani Hoon, you may ask us, "Toh phir problem kya hai?"

The problem plaguing this movie a la the caste system plaguing Laalgaon is a lack of subtlety. Unlike the filmmaking, the storytelling in Article 15 opens on a wonky note and stays there for its entirety. The movie is bookended by two songs that are so on the nose about the film's message that it is wholly evident that this is a story of an outsider looking in than an insider's account of the horrors of the caste system.

Ayushmann Khurrana is impeccable in his portrayal of the morally upstanding Ayan Ranjan. Ayan is always dressed to the nines. Ayan never comes off as holier than his surroundings. And Ayan's character is meant to hold a glancing mirror up to our kind while simultaneously making us feel good about the reflection of ourselves we see at the corners of our eyes. While we do appreciate the customary ego boost, what we as an audience don't get to observe are the inner machinations of Laalgaon's caste hierarchy and the ramifications it has on the people inhabiting it. And the lesser said about the movie's underwhelming murder investigation-fuelled parallel plot, the better.

Characters like Manoj Pahwa's excellently rendered Brahma Dutt, Kumud Mishra's strong yet submissive Jatav, Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub's straight-shooting Nishad and Sayani Gupta's wide-eyed Gaura all aim to paint a vivid picture of the film's unforgiving setting, but the writing fails them time and time again. The themes are illustrated at their best via smartly crafted visual metaphors and at their worst land clubby blows to your eardrums through ham-fisted dialogues. The movie loads itself with so much moral fibre that it is primed to go into your right ear and fall out of your left left before the weekend has passed with little to no fuss.

Remember those customary articles written about child labour in Sivakasi when every Diwali rolls around? So upstanding, so relevant and so heartbreaking, and yet the problem remains as forgotten as the newspaper after the festive season passes.

If that is the case, why do our own experiences with prejudice and films like Pariyerum Perumal stand the test of time when compared to a one and done affair like Article 15? The simplest answer we can glean after all this dissection is that our personal experiences and stories that germinate from a deeply personal standpoint have multiple perspectives. For example, I learnt to question blind faith in religion from an uncle who held up caste-based superstitions. He is a fully realised character who has both good and bad ideas. And with Pariyerum Perumal, you see the title character's shame and pride with regards to where he comes from and a whole host of upper-class characters who aim to help him in his journey while simultaneously dealing with their own prejudices.

These experiences and stories put us in the driver's seat and compel us to answer some hard questions. The answers don't come easy and the same answers don't work twice. Article 15's narrative doesn't tread on such dangerous territory. Its story is one that needs to be heard but not one that has staying power. Hence, the final shot of a group of policemen sharing a roti-laden meal may never match up to a shot of two tea cups tied together by a flower.

Nearly a year ago, my girlfriend and I spoke to both sets of parents about our relationship. For all the support they showed my cousins when they came clean about their relationships, one of the first concerns raised by my parents was, "We hope her family isn't too far down the caste ladder because it'll be a hard thing to justify to our relatives." Need I remind you, this happened in 2018.

As much as we city slickers try to turn the blind eye to it, prejudice does exist all around us. Your experience with it might be wholly different when compared to mine but denial is not an option. Ayushmann Khurrana's Ayan Ranjan, too, is one of us. A Delhi-bred, foreign-educated, millennial, woke, IPS officer that does not see caste. His first posting is to the sleepy, mist-filled, fictional town of Laalgaon in rural Uttar Pradesh. Akin to you and me, the townsfolk make the fictional Ayan aware of their locality's stringently upheld caste system with the use of both actions and words.

A day later, three teen girls, from one of the lower castes, are reported missing. A day after that, two of the three girls are found hung by the neck on a lonely tree. Armed with a police force that seems hellbent upon closing the case without a shred of investigation, Ayan takes it upon himself to deliver justice to the marginalised section of Laalgaon's population.

Both Ayan and the film he is in have universally beloved ideals. But simply having high ideals doesn't give a film a perfect score. High ideals need to be bolstered by high-level filmmaking and storytelling. Article 15 does the first part well right off the bat. The film's exquisite cinematography and sense of mood, tone and space set you up for the noir-inspired cinematic experience. The score is ominous, the shot division is pitch perfect, the set design and costumes are on point, and the social message being espoused is relevant to the present day.

In the vein of Sanjana's mom in Main Prem Ki Deewani Hoon, you may ask us, "Toh phir problem kya hai?"

The problem plaguing this movie a la the caste system plaguing Laalgaon is a lack of subtlety. Unlike the filmmaking, the storytelling in Article 15 opens on a wonky note and stays there for its entirety. The movie is bookended by two songs that are so on the nose about the film's message that it is wholly evident that this is a story of an outsider looking in than an insider's account of the horrors of the caste system.

Ayushmann Khurrana is impeccable in his portrayal of the morally upstanding Ayan Ranjan. Ayan is always dressed to the nines. Ayan never comes off as holier than his surroundings. And Ayan's character is meant to hold a glancing mirror up to our kind while simultaneously making us feel good about the reflection of ourselves we see at the corners of our eyes. While we do appreciate the customary ego boost, what we as an audience don't get to observe are the inner machinations of Laalgaon's caste hierarchy and the ramifications it has on the people inhabiting it. And the lesser said about the movie's underwhelming murder investigation-fuelled parallel plot, the better.

Characters like Manoj Pahwa's excellently rendered Brahma Dutt, Kumud Mishra's strong yet submissive Jatav, Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub's straight-shooting Nishad and Sayani Gupta's wide-eyed Gaura all aim to paint a vivid picture of the film's unforgiving setting, but the writing fails them time and time again. The themes are illustrated at their best via smartly crafted visual metaphors and at their worst land clubby blows to your eardrums through ham-fisted dialogues. The movie loads itself with so much moral fibre that it is primed to go into your right ear and fall out of your left left before the weekend has passed with little to no fuss.

Remember those customary articles written about child labour in Sivakasi when every Diwali rolls around? So upstanding, so relevant and so heartbreaking, and yet the problem remains as forgotten as the newspaper after the festive season passes.

If that is the case, why do our own experiences with prejudice and films like Pariyerum Perumal stand the test of time when compared to a one and done affair like Article 15? The simplest answer we can glean after all this dissection is that our personal experiences and stories that germinate from a deeply personal standpoint have multiple perspectives. For example, I learnt to question blind faith in religion from an uncle who held up caste-based superstitions. He is a fully realised character who has both good and bad ideas. And with Pariyerum Perumal, you see the title character's shame and pride with regards to where he comes from and a whole host of upper-class characters who aim to help him in his journey while simultaneously dealing with their own prejudices.

These experiences and stories put us in the driver's seat and compel us to answer some hard questions. The answers don't come easy and the same answers don't work twice. Article 15's narrative doesn't tread on such dangerous territory. Its story is one that needs to be heard but not one that has staying power. Hence, the final shot of a group of policemen sharing a roti-laden meal may never match up to a shot of two tea cups tied together by a flower.

ARTICLE 15 SNAPSHOT

-

Cast

-

Music

-

Director

-

TheatresNot screening currently in any theatres in Hyderabad.

ARTICLE 15 USER REVIEWS

1 - 1 OF 1 COMMENTS

1 USER

Performances

Script

Music/Soundtrack

Visuals

NA

NA

NA

NA

Can watch again - NA

Good for kids - NA

Good for dates - NA

Wait for OTT - NA

Believe it or not.. the first encounter I had with caste was with my marriage as well. I was forced to know my own caste at that point. When nothing else in life is driven by caste - why should marriage? ... I guess this is a topic that's been covered by various movies in various angles.

Back to the movie at hand .. if one feels that the actual plot was the murder investigation then the caste system was just the background score in the movie. All the other political stuff, the social issues etc. did not feel like they drove the plot, they are just there so that the hero's character gets some colour.

The flip side is if you feel that the plot was showing the caste system etc. then they should have explored this much more.. like showing a little more of "Mahantji". And the murder investigation just becomes noise in such a story.

I thought the script did not tie in both of these sides properly - except for 2 things - Kumud Mishra's Jatav and a statement made in the police station that talks about "aukaat".

Back to the movie at hand .. if one feels that the actual plot was the murder investigation then the caste system was just the background score in the movie. All the other political stuff, the social issues etc. did not feel like they drove the plot, they are just there so that the hero's character gets some colour.

The flip side is if you feel that the plot was showing the caste system etc. then they should have explored this much more.. like showing a little more of "Mahantji". And the murder investigation just becomes noise in such a story.

I thought the script did not tie in both of these sides properly - except for 2 things - Kumud Mishra's Jatav and a statement made in the police station that talks about "aukaat".

RATING

7

The prickly experiences dealing with caste-ism leaves us with are unforgettable. They either help you question the world around you or leave you believing that this is the way the world is and we shouldn't rock the boat. One is significantly worse than the other.

And I definitely agree with you. The film is trying to balance social commentary with a mystery and shortchanges the mystery element big time. Because it shortchanges the mystery so much, the film has no rewatch value. It is one and most definitely done. It is so intent on letting people know the right thing that it doesn't do right by itself.

If it weren't for the way it looked and the performances this might have become as poor a cinema watching experience as an after-school special.

And I definitely agree with you. The film is trying to balance social commentary with a mystery and shortchanges the mystery element big time. Because it shortchanges the mystery so much, the film has no rewatch value. It is one and most definitely done. It is so intent on letting people know the right thing that it doesn't do right by itself.

If it weren't for the way it looked and the performances this might have become as poor a cinema watching experience as an after-school special.

LEAVE A COMMENT

fullhyd.com has 700,000+ monthly visits. Tell Hyderabad what you feel about Article 15!

MORE MOVIES

Contemporary Reviews

SEARCH MOVIES

Dissatisfied with the results? Report a problem or error, or add a listing.

ADVERTISEMENT

SHOUTBOX!

{{ todo.summary }}... expand »

{{ todo.text }}

« collapse

First | Prev |

1 2 3

{{current_page-1}} {{current_page}} {{current_page+1}}

{{last_page-2}} {{last_page-1}} {{last_page}}

| Next | Last

{{todos[0].name}}

{{todos[0].text}}

ADVERTISEMENT

This page was tagged for

article 15 review fullhyderabad

article 15 full movie watch online

article 15 full HD

Article 15 hindi movie

Article 15 reviews