Satyagraha Review

Suggestions

Can watch again

No

Good for kids

No

Good for dates

No

Wait for OTT

Yes

"Face the nation", proclaims a popular news channel. The purported mood of a people is now instantly available. Some might say that the distance between the "neta" and the "janta" has diminished. The verbal parleying on prime-time news, with politicians and bureaucrats boxed in mini-screens, is a daily reminder of the changing mode of conversation between a nation and its leaders.

Social cinema, of the mainstream "Prakash Jha" variety, not only adopts this format of political communication as its subject, but also utilizes it to interact with (and attract) its viewers.

Owing to the current political climate of scams, scoundrels and such, a dialogue is established between Satyagraha and its audience through the course of the film. The "aam aadmi" discourse deployed by angry young-old man Amitabh Bachchan and hero-of-the-masses Ajay Devgn aims to resonate with urgent clarity, temporarily irking its middle-class viewers in the air-conditioned coolness of multiplexes.

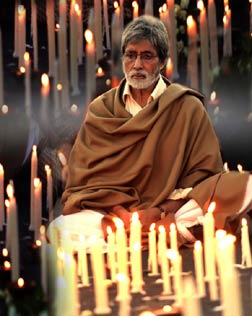

Satyagraha outlines the all-too-familiar present moment of public resentment against institutional corruption, and depicts the mobilisation of a nascent mass movement, stumbling but also rising in keen protest. Retired headmaster Dwarka Anand (Amitabh Bachchan) and his daughter-in-law Sumitra (Amrita Rao), driven to the edge by a personal tragedy, agitate against the corrupt regime of their zilla's collector.

Business tycoon Manav Raghavendra (Ajay Devgn), a family friend, joins them in their struggle, as does TV journalist Yasmin Ahmed (Kareena Kapoor). With the support of local goon Arjun Singh (Arjun Rampal) and a burgeoning youth, these citizen-rebels initiate a non-violent protest against the opportunistic reigning party, notably against its crafty minister, Balram Singh (Manoj Bajpai).

In similar vein, the film, No One Killed Jessica comes to mind, but there the mass awakening pertained to a specifically urban, upper-middle class.

In Jha's film, it is unclear whether the dissenting masses are restricted to the middle class. Satyagraha attempts to portray an inclusive mass movement, and as a symbolic token, a frenzied beggar is seen always dancing at the forefront of every public rally in the film.

The plot runs merely like a reminder of newspaper headings, bringing to memory, amongst other things, the murder of honest engineer Satyendra Dubey, the telecom scam, and the Anna Hazare agitation leading up to the formation of the Aam Aadmi Party. Jha must realize that a mish-mash of current events loosely strung together does not qualify as a story.

The script also harks back to historical moments of the nationalist movement such as the Chauri Chaura incident and Gandhi's "fast unto death". History is shown questioning the present.

Unfortunately, the story that unfolds is an ill-conceived one, engaging in parts but largely laboured. In the second-half of the film, as the revolution gathers momentum, event after event occurs, but it is all too hurried, and it seems as if Jha and co-writer Anjum Rajabali wish to cram in as many real-life occurrences as they possibly can.

The love angle between Yasmin and Manav is underdeveloped, as is the characterization of the main protagonists. The transformations that some characters undergo seem rather simplistic. The human drama, at times, slips into the territory of inept melodrama.

Despite all this, Satyagraha manages to plough through the dirt, thanks to power-packed performances by its actors, chiefly, Amitabh Bachchan and Manoj Bajpai. While the former recreates a Gandhi-like aura intensified by a seething restraint, the latter, with his wily smile and easy villainy, acts as a counterpoint to the film's heavy dialogue-baazi.

Ajay Devgn lends dignity to his role. Kareena Kapoor seems a tad over-made for a field journalist. She would have done greater justice had her character received more attention. Arjun Rampal is believable as the local goon with a heart of gold. The script forgets Amrita Rao altogether.

The music by Salim-Sulaiman is average. Janta Rocks does not leave us rocking. The rock/semi-classical love ballad, Ras Ke Bhare Tore Naina, is melodious even though it is squeezed into the narrative. Raghupati Raghav Raja Ram, on the other hand, is tweaked to perfection, and every time it plays, it gives one goosebumps.

To be fair, the film does succeed in raising pertinent dilemmas regarding political ideology and the whole nation-building exercise. Can personal emotions sustain nationalistic fervour? What constitutes martyrdom? Does the end justify the means? But these questions, by themselves, cannot surpass the perfunctory nature of the script.

Prakash Jha has travelled a great distance from his earlier socio-political films such as Damul and Pariniti. The likes of Raajneeti, Aarakshan, and now, Satyagraha, are sleeker and more refined in terms of production design, but lacking in the art of the story.

Is it, perhaps, a desire to play to the crowd?

Social cinema, of the mainstream "Prakash Jha" variety, not only adopts this format of political communication as its subject, but also utilizes it to interact with (and attract) its viewers.

Owing to the current political climate of scams, scoundrels and such, a dialogue is established between Satyagraha and its audience through the course of the film. The "aam aadmi" discourse deployed by angry young-old man Amitabh Bachchan and hero-of-the-masses Ajay Devgn aims to resonate with urgent clarity, temporarily irking its middle-class viewers in the air-conditioned coolness of multiplexes.

Satyagraha outlines the all-too-familiar present moment of public resentment against institutional corruption, and depicts the mobilisation of a nascent mass movement, stumbling but also rising in keen protest. Retired headmaster Dwarka Anand (Amitabh Bachchan) and his daughter-in-law Sumitra (Amrita Rao), driven to the edge by a personal tragedy, agitate against the corrupt regime of their zilla's collector.

Business tycoon Manav Raghavendra (Ajay Devgn), a family friend, joins them in their struggle, as does TV journalist Yasmin Ahmed (Kareena Kapoor). With the support of local goon Arjun Singh (Arjun Rampal) and a burgeoning youth, these citizen-rebels initiate a non-violent protest against the opportunistic reigning party, notably against its crafty minister, Balram Singh (Manoj Bajpai).

In similar vein, the film, No One Killed Jessica comes to mind, but there the mass awakening pertained to a specifically urban, upper-middle class.

In Jha's film, it is unclear whether the dissenting masses are restricted to the middle class. Satyagraha attempts to portray an inclusive mass movement, and as a symbolic token, a frenzied beggar is seen always dancing at the forefront of every public rally in the film.

The plot runs merely like a reminder of newspaper headings, bringing to memory, amongst other things, the murder of honest engineer Satyendra Dubey, the telecom scam, and the Anna Hazare agitation leading up to the formation of the Aam Aadmi Party. Jha must realize that a mish-mash of current events loosely strung together does not qualify as a story.

The script also harks back to historical moments of the nationalist movement such as the Chauri Chaura incident and Gandhi's "fast unto death". History is shown questioning the present.

Unfortunately, the story that unfolds is an ill-conceived one, engaging in parts but largely laboured. In the second-half of the film, as the revolution gathers momentum, event after event occurs, but it is all too hurried, and it seems as if Jha and co-writer Anjum Rajabali wish to cram in as many real-life occurrences as they possibly can.

The love angle between Yasmin and Manav is underdeveloped, as is the characterization of the main protagonists. The transformations that some characters undergo seem rather simplistic. The human drama, at times, slips into the territory of inept melodrama.

Despite all this, Satyagraha manages to plough through the dirt, thanks to power-packed performances by its actors, chiefly, Amitabh Bachchan and Manoj Bajpai. While the former recreates a Gandhi-like aura intensified by a seething restraint, the latter, with his wily smile and easy villainy, acts as a counterpoint to the film's heavy dialogue-baazi.

Ajay Devgn lends dignity to his role. Kareena Kapoor seems a tad over-made for a field journalist. She would have done greater justice had her character received more attention. Arjun Rampal is believable as the local goon with a heart of gold. The script forgets Amrita Rao altogether.

The music by Salim-Sulaiman is average. Janta Rocks does not leave us rocking. The rock/semi-classical love ballad, Ras Ke Bhare Tore Naina, is melodious even though it is squeezed into the narrative. Raghupati Raghav Raja Ram, on the other hand, is tweaked to perfection, and every time it plays, it gives one goosebumps.

To be fair, the film does succeed in raising pertinent dilemmas regarding political ideology and the whole nation-building exercise. Can personal emotions sustain nationalistic fervour? What constitutes martyrdom? Does the end justify the means? But these questions, by themselves, cannot surpass the perfunctory nature of the script.

Prakash Jha has travelled a great distance from his earlier socio-political films such as Damul and Pariniti. The likes of Raajneeti, Aarakshan, and now, Satyagraha, are sleeker and more refined in terms of production design, but lacking in the art of the story.

Is it, perhaps, a desire to play to the crowd?

SATYAGRAHA SNAPSHOT

-

Cast

-

Music

-

Director

-

TheatresNot screening currently in any theatres in Hyderabad.

SATYAGRAHA USER REVIEWS

Be the first to comment on Satyagraha! Just use the simple form below.

LEAVE A COMMENT

fullhyd.com has 700,000+ monthly visits. Tell Hyderabad what you feel about Satyagraha!

MORE MOVIES

Latest Reviews

Contemporary Reviews

SEARCH MOVIES

Dissatisfied with the results? Report a problem or error, or add a listing.

ADVERTISEMENT

SHOUTBOX!

{{ todo.summary }}... expand »

{{ todo.text }}

« collapse

First | Prev |

1 2 3

{{current_page-1}} {{current_page}} {{current_page+1}}

{{last_page-2}} {{last_page-1}} {{last_page}}

| Next | Last

{{todos[0].name}}

{{todos[0].text}}

ADVERTISEMENT

This page was tagged for

Satyagraha hindi movie

Satyagraha reviews

release date

Amitabh Bachchan, Ajay Devgn

theatres list